6. コヒーレントフォノン制御

固体結晶に対し、そのフォノン振動の周期よりも短い時間幅を持ったパルスレーザーを照射すると、結晶のフォノン運動を励起することができる。通常の熱で励起されるフォノンと異なり、 レーザー光が照射された領域内で原子(分子)の運動の位相が揃った状態で励起が行われるため、このようなフォノン振動をコヒーレントフォノンと呼ぶ。 コヒーレントフォノンを計測するには、pump-probe分光によって反射率の変化として計測することが一般的です。

6-1. ビスマス単結晶の二次元原子運動の制御と可視化

ビスマスの単位格子を図11に示す。z軸方向に振動するA1gモードとxy平面内で二重縮退したEgモードという二つのモードが存在して�いる。 これらのモードの励起振幅を光によって制御することができれば、結晶格子中の原子の運動を制御できることに繋がる。実験では、図12のような光学系を用い、ポンプ光の照射による プローブ光の反射率変化を測定している。

図11 ビスマスの単位格子とフォノンモード

図12 コヒーレントフォノン光学系

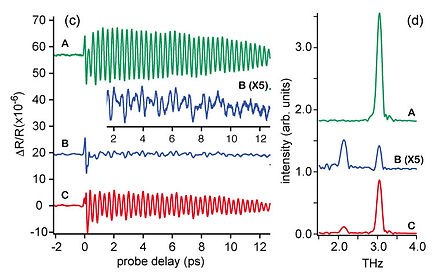

励起パルスとしてチャープパルスを時間的に重ねた励起パルスを用い、両者の遅延時間を制御することでTHz領域の変調をスペクトルに与え、フォノンの振幅制御をおこなっている。 さらにab initio計算によって反射率の変化と原子の変位の間の比例定数を計算し、反射率の変化から光の照射された平面内における原子の変位を可視化することに成功した。 より詳細を知りたい方は、以下の文献を参考にして下さい。

図13 フォノン振幅制御結果

6-2. ルブレン単結晶のTHzフォノン熱浴分布の制御

現在執筆中

【関連論文】

-

Optical manipulation of coherent phonons in superconducting YBa2Cu3O7-δ thin films

Y. Okano, H. Katsuki, Y. Nakagawa, H. Takahashi, K. G. Nakamura and K. Ohmori, Faraday Discussions 153, 375-382 (2011). -

All-Optical Control and Visualization of Ultrafast 2D Atomic Motions in a Single Crystal of Bismuth

H. Katsuki, J. C. Delagnes, K. Hosaka, K. Ishioka, H. Chiba, E. S. Zijlstra, M. E. Garcia, H. Takahashi, K. Watanabe, M. Kitajima, Y. Matsumoto, K. G. Nakamura, and K. Ohmori, Nature Communications 4:2801 doi:10.1038/ncomms3801 (2013). -

Mode Selective Excitation of THz vibrations in Single Crystalline Rubrene

K. Yano, H. Katsuki, and H. Yanagi,

J. Chem. Phys. 150, 054503 (2019).

3. Control of vibronic WPs in gas phase diatomic molecules

Iodine molecules have a small vibrational level spacing due to the heavy nuclear mass. Because of this, vibrational WPs can be generated easily by exciting electronic excited states with broadband fs laser pulse. As explained in the previous chapter, two Was generated in the electronic excited state interfere with each other. We need to shine another laser pulse (probe pulse) to retrieve the final WP state information. This kinds of pump-probe experiments are fundamental technique to observe ultrafast dynamics in a target system.

Fig.4 Experimental scheme of WP interferometry in iodine molecule

Fig. 4 shows the scheme of such experiments. The WPs generated by the pump and control pulses are further excited to the upper electronic state (E state) by the probe pulse. The fluorescence from E state is measured by the photo-multiplier.

We have performed two types of experiments, one with fs probe pulse and the other with nanosecond (ns) probe pulse. With ns probe pulse, we can selectively detect the population in one single eigenstate. On the other hand, we can visualize the temporal evolution of the WP by applying fs probe pulse. They are explained below.

3-1. Population read-out by ns probe pulse

The bandwidth of ns probe pulse is much narrower than the energy spacing between neighboring vibrational levels of iodine. Thus, we can observe the fluorescence signal only when the wavelength of the ns probe pulse is resonant with particular vibronic transition between E and B states. If we scan the wavelength of the ns probe pulse, we can perform the state-selective detection of the eigenstate involved in the WP. Fig. 5 shows the modulation of the population in v=33 level as we scan the delay τ between the pump and control pulses. This kind of interferometric modulation is called "Ramsey fringe." During the scan, the wavelength of the probe pulse os fixed. The delay τ is scanned about ±2fs around 500 fs, which corresponds to the classical vibrational period of the WP. The quality of the interference is over 90%, demonstrating that high quality interference is realized. The oscillation period is 1.8fs, which corresponds to the transition energy between v=0 in X(ground) state and v=33 in B state. Actually, the main goal of original Ramsey fringe spectroscopy is to determine the transition frequency from the period of observed fringes.

Fig.5 Ramsey fringe observation in iodine

By scanning the probe wavelength, we can visualize the population distribution and the relative phases of each eigenstate involved in the WP. As advanced application of this technique, we have performed discrete Fourier transform using vibrational WP, and also actively control the relative phases by utilizing strong nonresonant laser pulses.

3-2. Visualization of WP motion by fs probe pulse

When we use fs probe pulse, it is possible to detect the probabolity density around the particular internuclear distance. This "window" position is determined by the wavelength of the probe pulse. Thus, by scanning the probe wavelength it is possible to visualize the spato-temporal WP probability density. (Strictly speaking, what is detected is the product of probability density and transition moment and electric field intensity.)

Fig. 6 shows the spatio-temporal plots of the WP density when pump and control pulses are shined with τ ~1.5 Tvib. The timing is tuned with ~0.45 fs step (90º phase difference). Although the full range of the spatial axis is only 6 pm, we can observe the modulating probability distribution as the relative phase changes. For example, the ridge (around 334pm) in the 0º scan is totally inverted to the valley in the 180º scan.

Fig.6 Observation of quantum carpets in iodine

3-3. Quantum interferometry with strong non-resonant laser pulse

In preparation

The gas phase experiments described here are not continued in NAIST lab. If you want to know more details, see the publication list below.

【関連論文】

-

Visualizing picometric quantum ripples of ultrafast wave-packet interference

H. Katsuki, H. Chiba, B. Girard, C. Meier, and K. Ohmori, Science 311, 1589-1592 (2006). -

Real-time observation of phase-controlled molecular wave-packet interference

K. Ohmori, H. Katsuki, H. Chiba, M. Honda, Y. Hagihara, K. Fujiwara, Y. Sato, and K. Ueda, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 093002 (2006). -

READ and WRITE Amplitude and Phase Information by Using High-Precision Molecular Wave-Packet Interferometry

H. Katsuki, K. Hosaka, H. Chiba, and K. Ohmori, Phys. Rev. A 76, 013403 (2007). -

Actively tailored spatiotemporal images of quantum interference on the picometer and femtosecond scales

H. Katsuki, H. Chiba, C. Meier, B. Girard, and K. Ohmori, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 103602 (2009). -

Ultrafast Fourier transform with a femtosecond laser driven molecule

K. Hosaka, H. Shimada, H. Chiba, H. Katsuki, Y. Teranishi, Y. Ohtsuki, and K. Ohmori, Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 180501 (2010). -

Strong-Laser-Induced Quantum Interference

H. Goto, H. Katsuki, H. Ibrahim, H. Chiba, and K. Ohmori, Nature Phys. 7, 383-385 (2011).